This blog focuses on parallel lessons in aviation and in leadership. Imagine, for a moment, how life would be if employee relations problems, competitive challenges, insufficient budgets and outdated equipment were replaced by perfection in every respect. The leadership equivalent of sparkling skies and smooth air is a business environment devoid of these difficulties. Although it sounds wonderful, this situation is unlikely to exist.

Aviation, leadership and in fact life in general involve a series of challenges. As we encounter each challenge, we have a choice in the way that we respond. Our success is often determined by the approach we take and choices we make when the storm clouds billow in our path.

1. Acknowledge the likelihood of storms

Simply understanding and accepting that fact that in-flight weather cannot always be perfect – or that not every day as a leader will be ideal – serves as mental preparation and reduces stress. Realizing and acknowledging that storms will erupt or challenges will arise can arm an individual with a degree of alertness and minimize the impact of difficulties.

2. Understand personal limits

A new pilot is limited in his or her ability to navigate weather. An instrument rating - the aviation equivalent of an advanced degree – is required for flight in clouds or in low visibility conditions. Wise new pilots typically avoid situations that might result in an encounter with storm clouds. They impose personal limits to ensure safety. These may include flight within a limited geographic area, flights of shorter duration, or flying in the company of a more experienced pilot.

|

| Navigating storm clouds requires skill and strategy Photo by Lillian LeBlanc |

Less experienced leaders can also invoke the personal limit approach. These leaders can ensure that they have readily available mentors and quickly seek assistance when faced with any new situation. In addition, new leaders can choose to defer decisions to more experienced leaders (their own bosses), with very clear indication that they will use the opportunity to observe and learn from the approach of the more seasoned individual.

3. Consider all factors when choosing the path forward

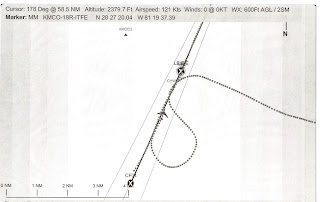

Navigating storm clouds requires a deep understanding of the weather, a full grasp of the capabilities (and limitations) of the aircraft and crew and a healthy dose of caution. Deviating well off course or a changing altitude may be necessary to ensure a safe and comfortable flight. A savvy aviator gathers all available information and carefully assesses the situation at hand to arrive at the best navigational decision.

Leaders must be nimble and flexible. Two seemingly similar situations can rarely be approached the same way. A simple employee relations matter or a product malfunction could appear, on the surface to be a case of déjà vu, but differences in personalities, timing or peripheral business conditions will influence the appropriate course of action. Responding to a leadership situation based solely on “been there, done that,” carries a high likelihood of failure.

4. Never be afraid to turn back and land

Not all storm clouds can be safely traversed by even the most skilled pilots. Occasionally, a pilot will continue a flight into conditions that are far worse than expected. As difficult as it may be, a course reversal may be warranted. Such a decision may result in disappointed passengers, missed appointments or extra expense. A few pilots stubbornly plod along into severe weather simply to avoid these problems. Sadly, some fail to live to tell about it.

Leadership decisions seldom involve life and death in the literal sense. However, leaders can find themselves in situations that call for a reversal of a decision. Altering course, perhaps requiring the leader to admit an error, may be extremely difficult and possibly embarrassing. However, failing to do so could result in serious damage or even derailment of an otherwise promising career. In the leader’s case as well as in the pilot’s case, the wisdom of the decision to change course may never be able to be validated.

Bright sunny days are a pilot’s dream. Happy employees and problem-free operations are wonderful for leaders. As pleasant as these times are, the realities of life enable storm clouds to brew. The best pilots and the most skilled leaders accept these conditions, while learning and understanding the most effective ways to manage them.

For additional reading on this topic, consider Severe Weather Flying by Dennis Newton and The Stress Effect – Why Smart Leaders Make Dumb Decisions and What to do About It. The former offers pilots valuable advice on the subject of thunderstorm and windshear avoidance. The latter is filled with practical strategies to make better decisions by understanding one’s own situation.